1.

O sol se põe por trás das montanhas,

a terra esfria.

Um estranho amarra seu cavalo a um castanheiro nu.

O cavalo está quieto — vira a cabeça de repente,

ouvindo, ao longe, o som do mar.

Preparo minha cama para passar a noite aqui,

estendendo minha colcha mais pesada sobre a terra úmida.

O som do mar —

quando o cavalo vira a cabeça, posso ouvi-lo.

Numa trilha entre castanheiros nus,

um cãozinho segue seu dono.

O cãozinho — ele não costumava correr na frente,

esticando a coleira, como se quisesse mostrar ao dono

o que vê ali, ali adiante —

o futuro, o caminho, chame como quiser.

Atrás das árvores, ao entardecer, é como um grande incêndio

ardendo entre duas montanhas,

de modo que a neve no pico mais alto

parece, por um momento, também arder.

Ouça: no fim da trilha, o homem chama.

Sua voz se tornou estranha agora,

a voz de alguém que chama o que não pode ver.

Repetidas vezes, ele grita por entre os castanheiros escuros.

Até que o animal responde,

ao longe, com um som tênue,

como se aquilo que tememos

não fosse terrível.

Crepúsculo: o estranho desamarra seu cavalo.

O som do oceano —

agora, apenas memória.

2.

O tempo passou, transformando tudo em gelo.

Sob o gelo, o futuro se agitava.

Se caíssemos nele, morreríamos.

Foi um tempo

de espera, de ação suspensa.

Eu vivia no presente, que era

aquela parte do futuro que podíamos ver.

O passado flutuava acima da minha cabeça,

como o sol e a lua, visível mas inatingível.

Foi um tempo

regido por contradições, como em

eu não sinto nada e

eu tenho medo.

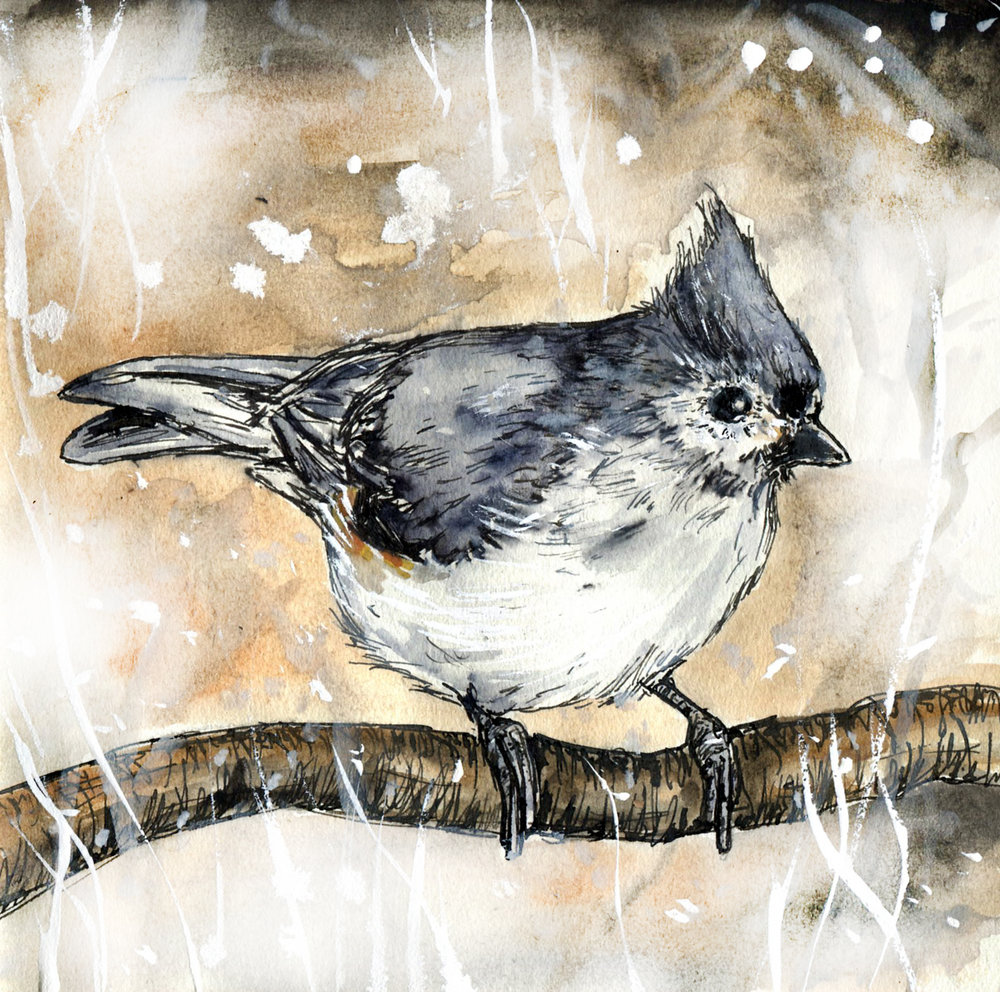

O inverno esvaziou as árvores, depois as encheu de neve.

Porque eu não sentia, a neve caiu, o lago congelou.

Porque eu tinha medo, não me movi;

minha respiração era branca, uma descrição do silêncio.

O tempo passou, e parte dele se tornou isto.

E parte simplesmente evaporou;

podíamos vê-la flutuar sobre as árvores brancas

formando partículas de gelo.

Toda a sua vida, você esperou pelo momento propício.

Então o momento propício

se revelou como o ato em si.

Eu via o passado se mover, uma linha de nuvens avançando

da esquerda para a direita ou da direita para a esquerda,

dependendo do vento. Alguns dias

não havia vento. As nuvens pareciam

permanecer onde estavam,

como uma pintura do mar, mais imóveis que reais.

Alguns dias, o lago era uma película de vidro.

Sob o vidro, o futuro emitia

sons discretos, convidativos:

era preciso se conter para não escutar.

O tempo passou; você pôde ver um pedaço dele.

Os anos que levou foram anos de inverno;

não fariam falta. Alguns dias

não havia nuvens, como se

as fontes do passado houvessem desaparecido. O mundo

perdera seu colorido, como um negativo; a luz passava

diretamente por dele. Então

a imagem esmaecia.

Acima do mundo

havia apenas o azul, azul por toda parte.

3.

No fim do outono, uma jovem ateou fogo a um campo

de trigo. O outono

fora muito seco; o campo

ardeu como um pavio.

Depois não restou nada.

Você caminha por ele, não vê nada.

Não há o que colher, nem o que cheirar.

Os cavalos não compreendem —

Onde está o campo?, parecem dizer.

Do mesmo modo que você e eu diríamos:

onde está o lar?

Ninguém sabe como responder.

Não restou nada;

só resta esperar, pelo bem do fazendeiro,

que o seguro cubra.

É como perder um ano de nossas vidas.

A que entregaríamos um ano de nossas vidas?

Depois, você volta ao antigo lugar —

tudo o que resta é carvão: negrume e vazio.

Você pensa: como pude viver aqui?

Mas era diferente então,

até mesmo no verão passado. A terra se comportava

como se nada pudesse dar errado.

Um fósforo foi o suficiente.

Mas no tempo certo — precisava ser no tempo certo.

O campo ressequido, seco —

a morte já instalada,

por assim dizer.

4.

Adormeci em um rio, acordei em um rio,

de meu misterioso

fracasso em morrer nada posso

dizer, nem

quem me salvou, nem por que razão —

Havia um imenso silêncio.

Nenhum vento. Nenhum som humano.

O século amargo

chegara ao fim, o glorioso se fora, o perene se fora,

o sol frio

persistindo como uma espécie de curiosidade, uma lembrança,

o tempo fluindo atrás dele —

O céu parecia muito limpo,

como no inverno,

o solo seco, não cultivado,

a luz oficial movendo-se

calmamente por uma fenda no ar

digna, complacente,

dissolvendo a esperança,

subordinando imagens do futuro a sinais de sua partida —

Acho que devo ter caído.

Quando tentei me levantar, tive de me forçar,

não acostumada à dor física —

Esquecera

a dureza dessas condições:

a terra não obsoleta

mas imóvel, o rio frio, raso —

Do meu sono, nada

lembro. Quando eu gritava

minha própria voz me acalmava, inesperadamente.

No silêncio da consciência, perguntei-me:

por que rejeitei minha vida? E respondi:

Die Erde überwältigt mich:

a terra me subjuga.

Tentei ser precisa nesta descrição

caso alguém venha depois de mim. Posso afirmar que,

quando o sol se põe no inverno, é

incomparavelmente belo e a memória disso

dura muito. Acho que isso quer dizer

que não houve noite.

A noite estava dentro de mim.

5.

Depois que o sol se pôs,

cavalgamos depressa, na esperança de encontrar

abrigo antes da escuridão.

Eu já podia ver as estrelas,

primeiro no céu oriental:

cavalgávamos, portanto,

na direção oposta à da luz

e rumo ao mar, pois

eu ouvira falar que lá havia uma vila.

Depois de algum tempo, começou a nevar.

Não muito, a princípio, depois

de forma constante, até que a terra

se cobriu de uma película branca.

O caminho percorrido aparecia

claramente quando eu virava a cabeça —

por um instante traçava

uma linha escura pela terra —

Então a neve se espessou, o caminho sumiu.

O cavalo estava cansado e faminto;

não conseguia mais encontrar

solo firme em parte alguma. Eu disse a mim mesma:

já estive perdida antes, já senti frio antes.

A noite veio até mim

exatamente assim, como um presságio —

e pensei: se eu tiver de

voltar aqui, gostaria de voltar

como ser humano, o meu cavalo

como ele mesmo. Caso contrário,

eu não saberia como começar de novo.

Trad.: Nelson Santander

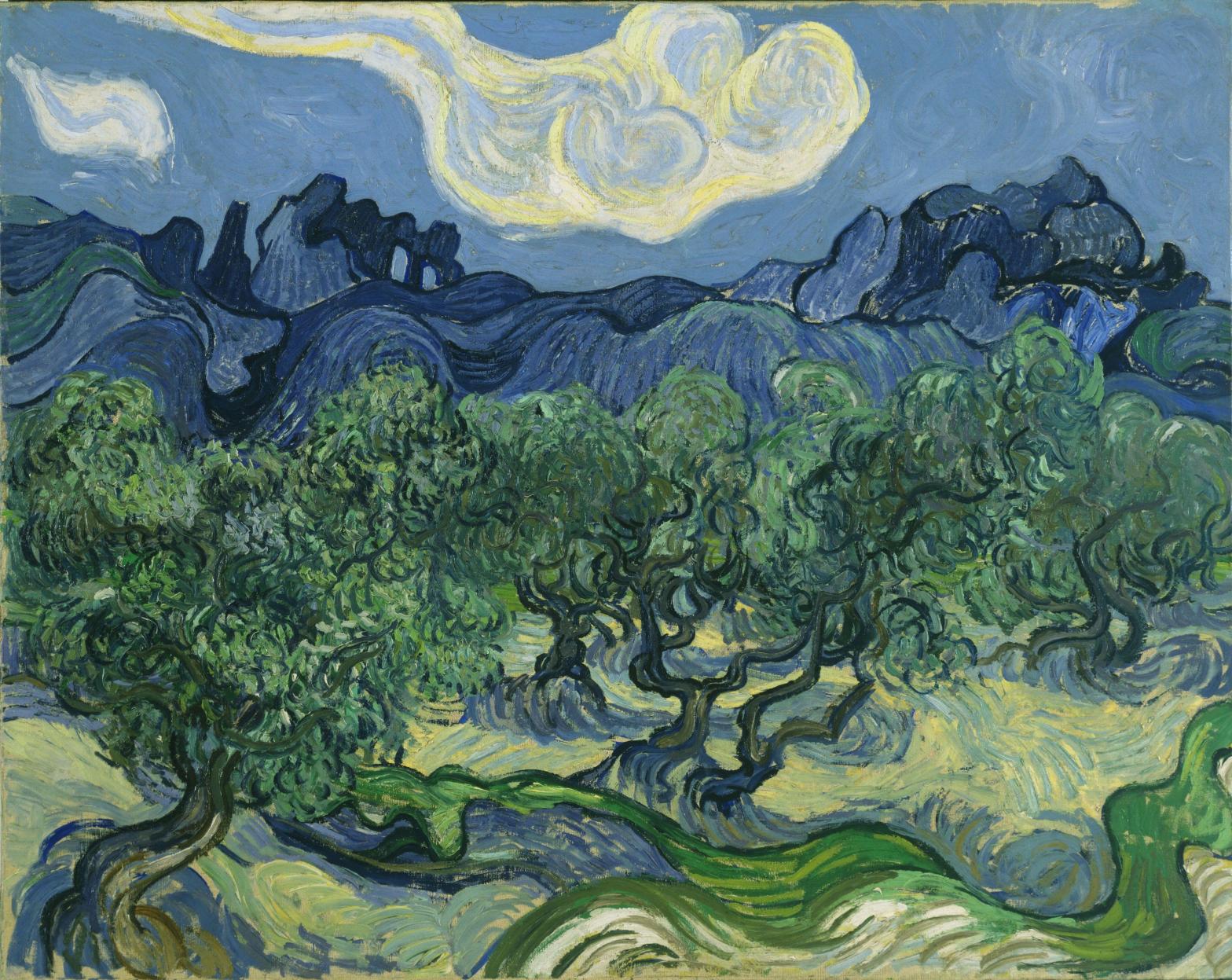

Landscape

1.

The sun is setting behind the mountains,

the earth is cooling.

A stranger has tied his horse to a bare chestnut tree.

The horse is quiet – he turns his head suddenly,

hearing, in the distance, the sound of the sea.

I make my bed for the night here,

spreading my heaviest quilt over the damp earth.

The sound of the sea —

when the horse turns its head, I can hear it.

On a path through the bare chestnut trees,

a little dog trails its master.

The little dog – didn’t he used to rush ahead,

straining the leash, as though to show his master

what he sees there, there in the future —

the future, the path, call it what you will.

Behind the trees, at sunset, it is as though a great fire

is burning between two mountains

so that the snow on the highest precipice

seems, for a moment, to be burning also.

Listen: at the path’s end the man is calling out.

His voice has become very strange now,

the voice of a person calling to what he can’t see.

Over and over he calls out among the dark chestnut trees.

Until the animal responds

faintly, from a great distance,

as though this thing we fear

were not terrible.

Twilight: the stranger has untied his horse.

The sound of the sea —

just memory now.

2.

Time passed, turning everything to ice.

Under the ice, the future stirred.

If you fell into it, you died.

It was a time

of waiting, of suspended action.

I lived in the present, which was

that part of the future you could see.

The past floated above my head,

like the sun and moon, visible but never reachable.

It was a time

governed by contradictions, as in

I felt nothing and

I was afraid.

Winter emptied the trees, filled them again with snow.

Because I couldn’t feel, snow fell, the lake froze over.

Because I was afraid, I didn’t move;

my breath was white, a description of silence.

Time passed, and some of it became this.

And some of it simply evaporated;

you could see it float above the white trees

forming particles of ice.

All your life, you wait for the propitious time.

Then the propitious time

reveals itself as action taken.

I watched the past move, a line of clouds moving

from left to right or right to left,

depending on the wind. Some days

there was no wind. The clouds seemed

to stay where they were,

like a painting of the sea, more still than real.

Some days the lake was a sheet of glass.

Under the glass, the future made

demure, inviting sounds:

you had to tense yourself so as not to listen.

Time passed; you got to see a piece of it.

The years it took with it were years of winter;

they would not be missed. Some days

there were no clouds, as though

the sources of the past had vanished. The world

was bleached, like a negative; the light passed

directly through it. Then

the image faded.

Above the world

there was only blue, blue everywhere.

3.

In late autumn a young girl set fire to a field

of wheat. The autumn

had been very dry; the field

went up like tinder.

Afterward there was nothing left.

You walk through it, you see nothing.

There’s nothing to pick up, to smell.

The horses don’t understand it-

Where is the field, they seem to say.

The way you and I would say

where is home.

No one knows how to answer them.

There is nothing left;

you have to hope, for the farmer’s sake,

the insurance will pay.

It is like losing a year of your life.

To what would you lose a year of your life?

Afterward, you go back to the old place—

all that remains is char: blackness and emptiness.

You think: how could I live here?

But it was different then,

even last summer. The earth behaved

as though nothing could go wrong with it.

One match was all it took.

But at the right time – it had to be the right time.

The field parched, dry—

the deadness in place already

so to speak.

4.

I fell asleep in a river, I woke in a river,

of my mysterious

failure to die I can tell you

nothing, neither

who saved me nor for what cause—

There was immense silence.

No wind. No human sound.

The bitter century

was ended,

the glorious gone, the abiding gone,

the cold sun

persisting as a kind of curiosity, a memento,

time streaming behind it—

The sky seemed very clear,

as it is in winter,

the soil dry, uncultivated,

the official light calmly

moving through a slot in air

dignified, complacent,

dissolving hope,

subordinating images of the future to signs of the future’s passing—

I think I must have fallen.

When I tried to stand, I had to force myself,

being unused to physical pain—

I had forgotten

how harsh these conditions are:

the earth not obsolete

but still, the river cold, shallow—

Of my sleep, I remember

nothing. When I cried out,

my voice soothed me unexpectedly.

In the silence of consciousness I asked myself:

why did I reject my life? And I answer

Die Erde überwältigt mich:

the earth defeats me.

I have tried to be accurate in this description

in case someone else should follow me. I can verify

that when the sun sets in winter it is

incomparably beautiful and the memory of it

lasts a long time. I think this means

there was no night.

The night was in my head.

5.

After the sun set

we rode quickly, in the hope of finding

shelter before darkness.

I could see the stars already,

first in the eastern sky:

we rode, therefore,

away from the light

and toward the sea, since

I had heard of a village there.

After some time, the snow began.

Not thickly at first, then

steadily until the earth

was covered with a white film.

The way we traveled showed

clearly when I turned my head—

for a short while it made

a dark trajectory across the earth—

Then the snow was thick, the path vanished.

The horse was tired and hungry;

he could no longer find

sure footing anywhere. I told myself:

I have been lost before, I have been cold before.

The night has come to me

exactly this way, as a premonition—

And I thought: if I am asked

to return here, I would like to come back

as a human being, and my horse

to remain himself. Otherwise

I would not know how to begin again.