-

Merrit Malloy – Epitáfio

“Epitáfio”, um poema de Merrit Malloy que explora com delicadeza a continuidade do amor após a morte, oferecendo uma visão tocante sobre a doação de si mesmo e o legado que vai além das palavras.

-

Maria do Rosário Pedreira – ouvidos

“Ouvidos”, de Maria do Rosário Pedreira: uma emotiva reflexão sobre a solidão e a saudade.

-

José Emílio Pacheco – Crianças e adultos

“Crianças e Adultos”, um poema de José Emílio Pacheco que explora a fragilidade da vida adulta e a eterna luta entre a inocência perdida e os medos que permanecem ocultos sob a superfície da maturidade.

-

Juana Bignozzi – [agora que estou velha]

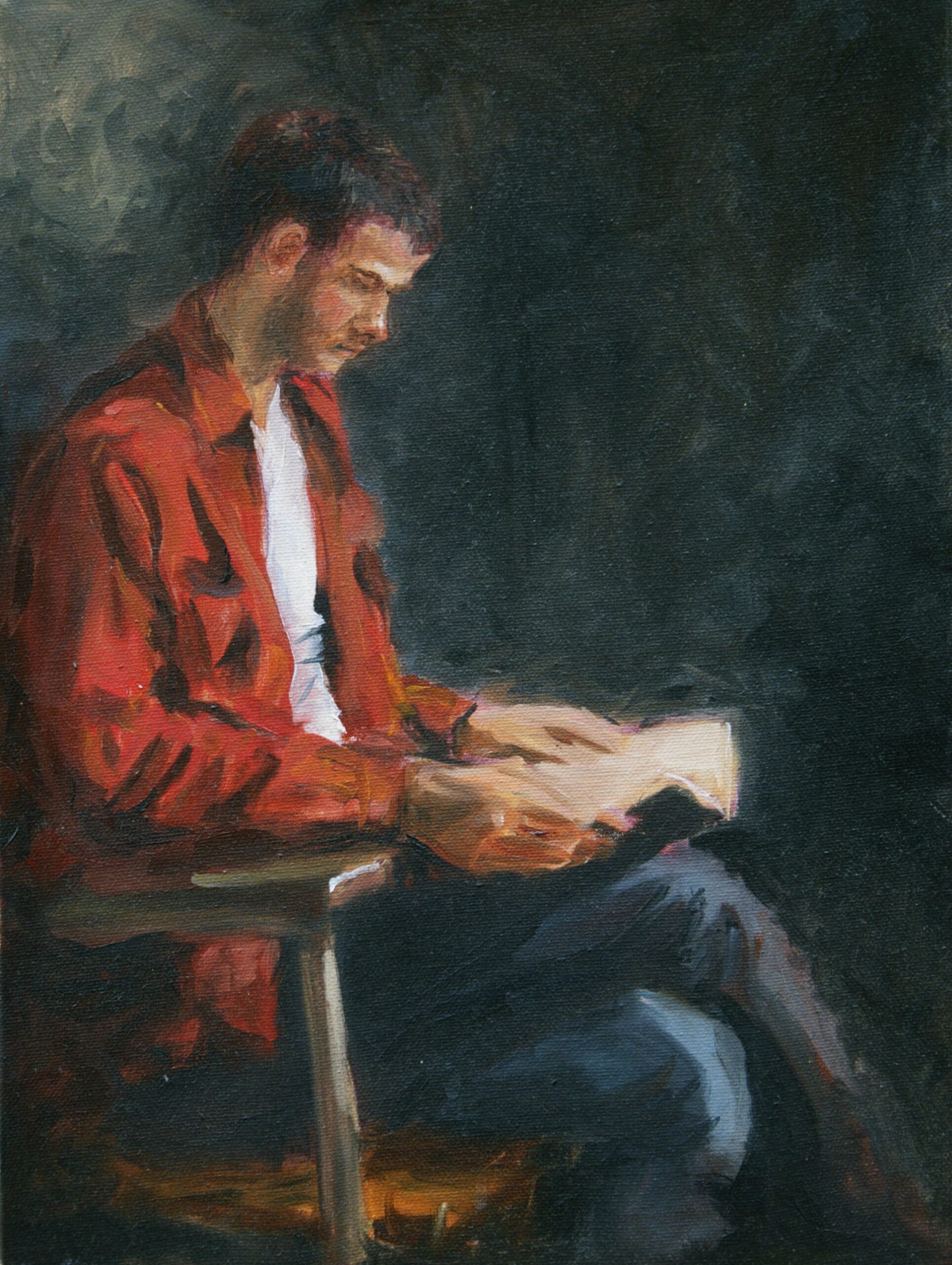

![Juana Bignozzi – [agora que estou velha]](https://singularidadepoetica.art/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/1e657a3b-c88c-4d30-8dfe-7155599c945f.jpg)

agora que estou velhae és um senhor idosogostaria que recordasses apenasdas fotos das viagensdos vestidos leves e floridosque eu usava entre os opulentos jardinse entre as ruínasagora que antes de adormecersem que percebas te toco para ver se ainda respiras Trad.: Nelson Santander Mais do que uma leitura, uma experiência. Clique, compre e contribua para…

-

Juan Vicente Piqueras – Ristorante dal 1882–

“Ristorante dal 1882-“, um poema de Juan Vicente Piqueras que evoca a nostalgia de encontros passados, entrelaçando risos e memórias, enquanto reflete sobre a fragilidade do tempo e a inevitabilidade de despedidas.

-

Adam Zagajewski – Uma chama

Senhor, dai-nos um longo invernomúsica suave, bocas pacientes,e um pouco de orgulho — antesque nossa era termine.Dai-nos assombroe uma chama, alta e brilhante. Trad.: Nelson Santander a partir da versão do poema em inglês traduzido por Clare Cavanagh Mais do que uma leitura, uma experiência. Clique, compre e contribua para manter a poesia viva em…

-

Alfonso Brezmes – Notas marginais

“Notas Marginais”, um poema de Alfonso Brezmes que revela como o tempo transforma as marcas do passado e o sentido das memórias.

-

Thom Gunn – Versos para o meu 55º aniversário

O amor dos idosos tem pouco valor,É desolado e seco até no ardor.Não dá pra saber o que é entusiasmoe o que é um involuntário espasmo. Trad.: Nelson Santander Mais do que uma leitura, uma experiência. Clique, compre e contribua para manter a poesia viva em nosso blog Lines for My 55th Birthday The love…

-

Carlos Montemayor – Memória

*”Memória”*, um poema de Carlos Montemayor sobre a quietude das coisas simples, a contemplação do tempo e o profundo silêncio que habita as lembranças da infância…

-

Linda Pastan – O dia mais feliz

“O dia mais feliz” de Linda Pastan revela a sutil beleza dos dias comuns, que muitas vezes passam despercebidos em meio à rotina cotidiana, convidando o leitor a refletir sobre a efemeridade da felicidade.