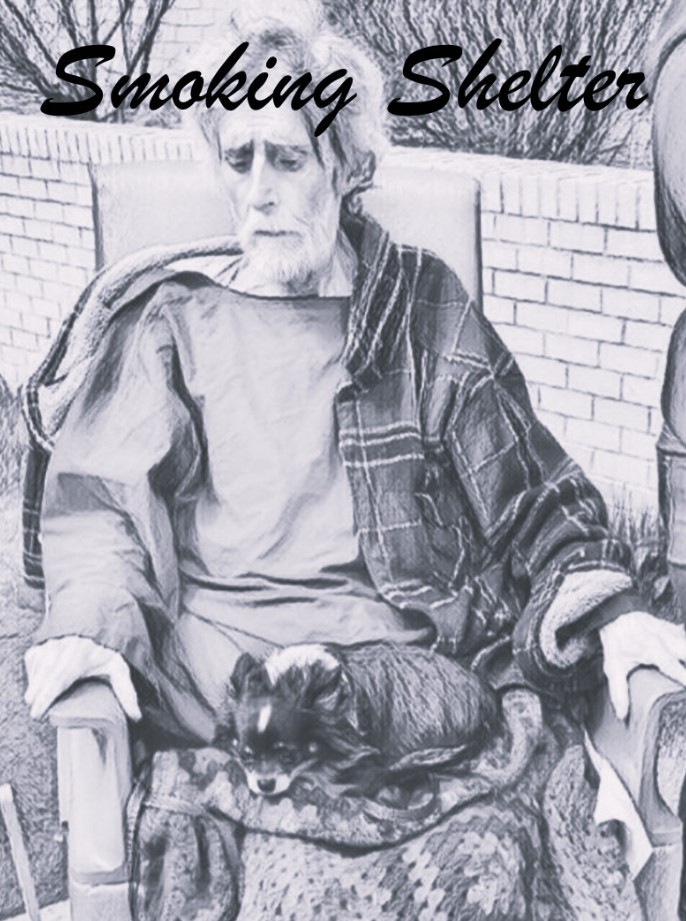

Área de fumantes

VA Medical Center em Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania: lado de fora da enfermaria

Páscoa, e o recinto de vidro está embaçado

como um olho remelento. Os velhos fumam,

ofegantes em seus bonés e cadeiras de rodas.

Trouxemos o cachorro do meu pai. Eu sei que não é

um cachorro de homem, anuncia ele, o chihuahua

repousando na colcha azul cobrindo seu colo.

De qualquer forma, é um ótimo cachorro, diz Cecil,

com seu baixo ronco rouco e catarrento.

Ele parece ter o tamanho certo para uma bola de futebol.

Perdemos a última. O que começa como uma risada

em ambas as gargantas se transforma em tosse áspera e depois úmida,

ecos de um poço profundo. Meu pai diz:

Ouvi dizer que em outubro não poderemos

mais fumar aqui. Ele olha para mim.

Você vai me tirar daqui antes disso, certo?

Mas antes que eu possa responder, outro

homem sentado em uma cadeira se aproxima lentamente,

e diz ao meu pai: Você se parece com Jesus.

Acho que consigo ver. O cabelo, a barba,

o ar faminto, a pele pálida, pergaminho

estirado finamente sobre ornamentos de madeira.

Você sofre como ele, o homem continua.

Mas eu não posso curar vocês, meu pai responde.

Queria poder. Outro acesso de tosse.

Precisa de alguma coisa? minha mãe pergunta, pegando

sua bolsa. Sim, ele diz, limpando a boca

com a mão trêmula. Um comprimido de Enditol.

Eu me pergunto: Qual será seu último prazer?

A vista do estacionamento, algumas tragadas, a brisa quente,

o cheiro de frango de um posto de combustível?

Ele se levanta e anda, e percebo que cada coisa

se abre em seu próprio ritmo — nossos corações, as primeiras

flores da primavera, mulheres indo à igreja com chapéus amarelos.

Trad.: Nelson Santander

Smoking Shelter

Outside the hospice ward of the VA Medical Center in Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania

Easter, and the glass enclosure’s clouded

like a rheumy eye. Old men are smoking,

wheezing in their service hats and wheelchairs.

We’ve brought my father’s dog. I know it’s not

a man’s dog, he announces, chihuahua

resting on the blue quilt draped on his lap.

That’s a great dog anyway, says Cecil,

his rumbling basso hoarse with settled phlegm.

Looks about the right size for a football.

We lost our last one. What starts as laughter

in both throats turns to rasping, then wet coughs,

echoes from a deep well. My father says,

I hear come October we’re not allowed

to smoke here anymore. He looks at me.

You’ll get me out of here before then, right?

But before I can answer, another

chair-bound man slowly scoots over to us,

tells my father, You look just like Jesus.

I guess I can see it. The hair, the beard,

the starvation, sallow skin, scroll parchment

stretched thinly over wooden finials.

You suffer like he did, he continues.

But I can’t heal you guys, my father says.

I wish I could. Another coughing fit.

You need something? my mother asks, reaching

in her purse. Yeah, he says, wiping his mouth

with a trembling hand. An Enditol pill.

I wonder, What will be your last pleasure?

A parking lot view, a few puffs, warm breeze,

smelling secondhand gas station chicken?

He is risen, and I realize each thing

opens at its own pace—our hearts, the first

spring blooms, church-bound women in yellow hats.